A journey down the Nile River is more than just a boat ride; it is a voyage through time. As the lifeblood of Ancient Egypt, the Nile has witnessed the rise and fall of dynasties, the construction of colossal monuments, and the unfolding of a civilization that continues to captivate the modern world. For thousands of years, the river’s banks served as a monumental canvas for the pharaohs, who built magnificent temples to honor their gods, commemorate victories, and ensure their immortality. To float on its waters is to travel through a living history book, where each bend reveals another testament to the grandeur of the past.

Our journey begins in Upper Egypt, a region of arid beauty and profound historical significance. The southern stretch of the Nile is a cradle of ancient faith and power, where temples were carved directly into rock cliffs or built with meticulous precision to align with the movements of the cosmos. As our felucca, a traditional wooden sailboat, glides northward, the sun glints off the sandstone, and the monumental scale of these sanctuaries begins to reveal itself.

Abu Simbel: The Sentinels of the South

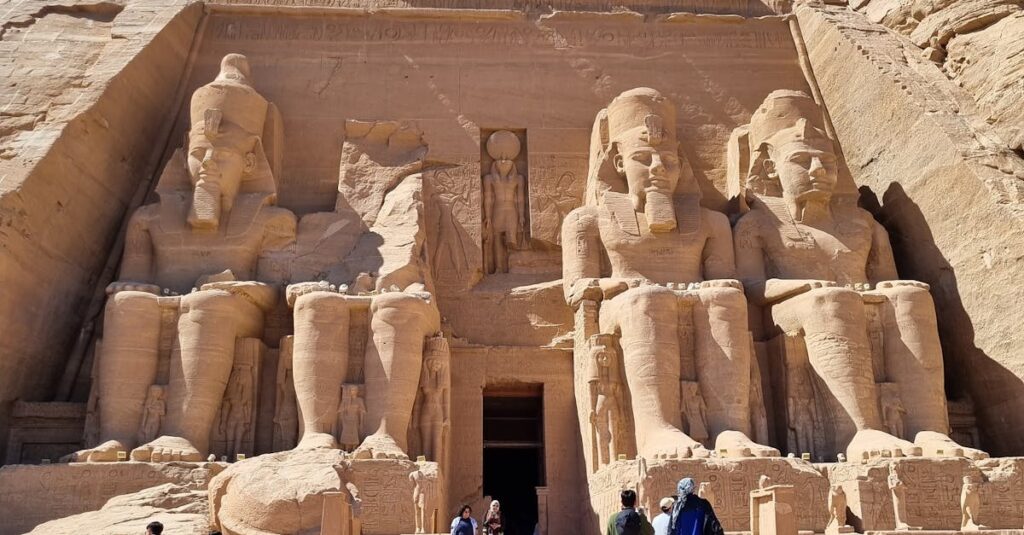

Our first major stop is the awe-inspiring Abu Simbel . Located far to the south, near the border with modern-day Sudan, these two temples are a breathtaking introduction to the power of Ramses II, one of Egypt’s most prolific builders. The main temple, dedicated to the gods Ra-Horakhty, Amun, and Ptah, is guarded by four colossal seated statues of Ramses himself, each over 20 meters high. The sheer scale of these figures is intended to intimidate and impress, asserting the pharaoh’s divine authority. Inside, the temple’s halls are a visual narrative of Ramses’ military triumphs, most notably the Battle of Kadesh.

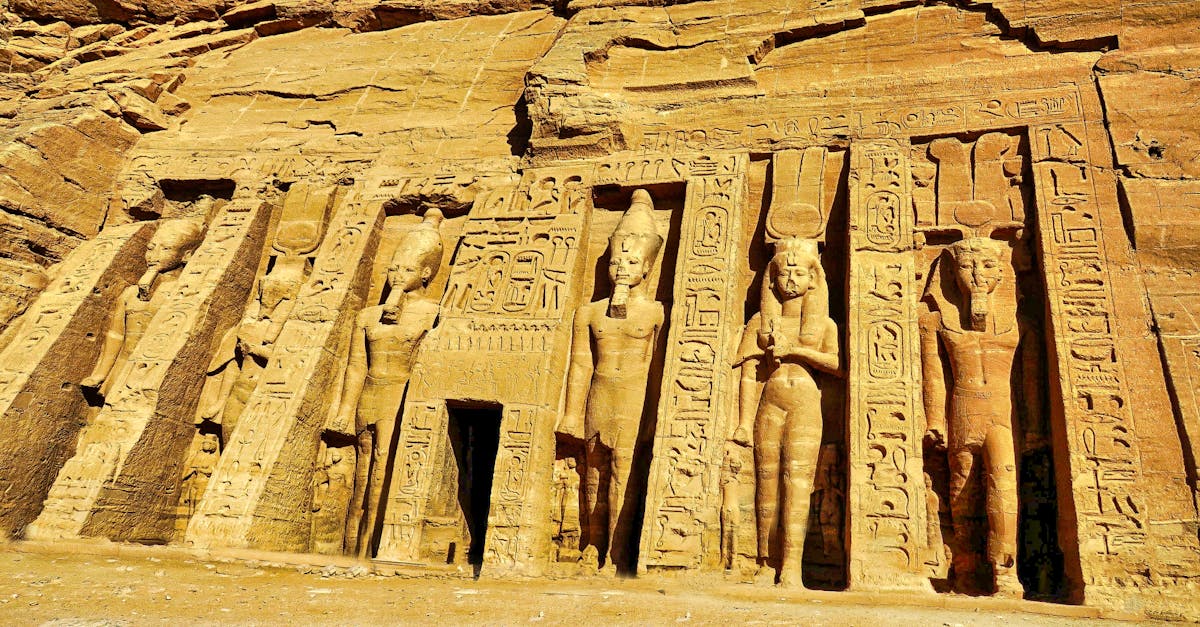

Next to the main temple is the smaller temple dedicated to his beloved queen, Nefertari, and the goddess Hathor. It is 8a rare instance where a queen is given an equal footing in a pharaonic monument of this magnitude. What makes Abu Simbel truly unique, however, is not its original construction, but its modern preservation. In the 1960s, a UNESCO team dismantled and relocated the entire complex to save it from being submerged by the Aswan High Dam. This incredible feat of modern engineering underscores the global value placed on these irreplaceable relics.

Philae: The Pearl of the Nile

Continuing north, we reach the city of Aswan, where the elegant Philae Temple complex awaits. This temple, dedicated to the goddess Isis, is often called the “Pearl of the Nile.” It was a major pilgrimage site for both ancient Egyptians and Romans, and its cult of Isis continued long after Christianity spread through the region. The temple’s beautiful pylons, hypostyle halls, and colonnades were painstakingly relocated to a higher island in the 1970s to save them from rising waters, much like Abu Simbel. Today, it stands as a testament to the perseverance of ancient beliefs and the collaboration of modern preservation efforts. The temple’s unique blend of Egyptian and Greco-Roman art and architecture, visible in its detailed reliefs and inscriptions, tells a fascinating story of cultural exchange.

Kom Ombo: A Temple for Two Gods

Our journey continues to the tranquil setting of Kom Ombo, a temple with a distinctive feature: it is a dual temple. This unique structure is dedicated to two gods: Sobek, the crocodile god of fertility and creation, and Horus the Elder, the falcon-headed god of the sky. The temple is perfectly symmetrical, with two entrances, two separate halls, and two sanctuaries. This duality is reflected in the reliefs, where scenes on one side depict rituals for Sobek, while the other side shows similar acts for Horus. The temple’s location on a high sand dune overlooking the Nile adds to its serene beauty. In ancient times, the Nile’s yearly flood would bring crocodiles to the very banks of the temple, a powerful visual for the worshipers of Sobek. The site also contains a well-preserved “nilometer,” a structure used to measure the river’s water level, a crucial task for managing agriculture in the region.

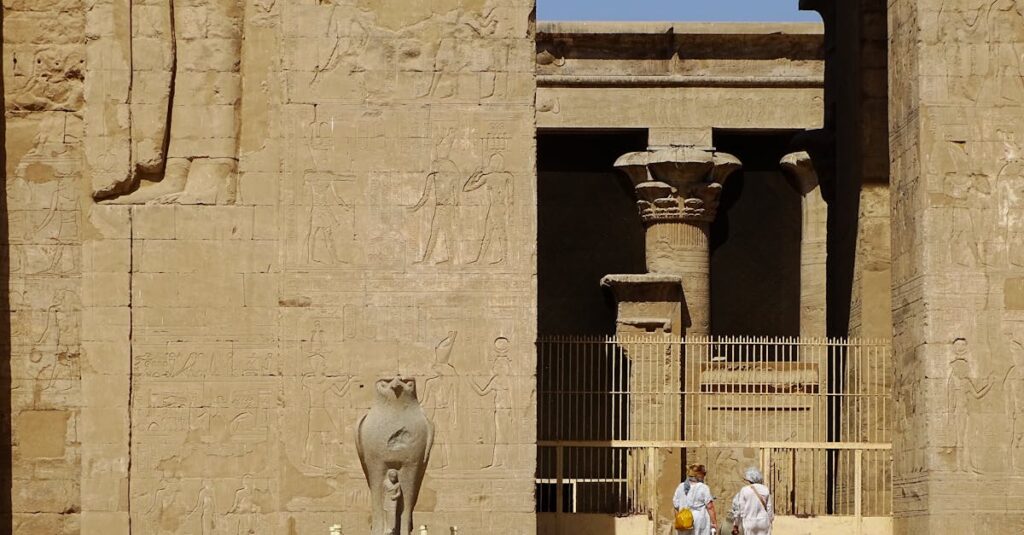

Edfu: The Sanctuary of Horus

Further north, we encounter the magnificent Temple of Edfu, one of the best-preserved ancient monuments in Egypt. Dedicated to the falcon god Horus, this temple was built during the Ptolemaic period but adheres strictly to the architectural style of the New Kingdom. Its remarkable state of preservation is a result of being buried under sand for centuries, which protected its intricate reliefs and structure from the elements. The temple’s walls are a rich source of information about ancient Egyptian religion and mythology, featuring the story of Horus’s mythological battle against his evil uncle Seth. The massive entrance pylons and the grand courtyard lead to inner sanctuaries that feel both grand and sacred. The hieroglyphs here are particularly well-preserved, providing invaluable insights into temple rituals and the roles of priests and pharaohs.

Luxor and Karnak: The Great Temples of Thebes

As we reach the former ancient capital of Thebes, now the city of Luxor, the scope of monumental architecture expands dramatically. The Luxor Temple and the Karnak Temple are not just two separate sites; they were once connected by a mile-long Avenue of Sphinxes.

Luxor Temple, built largely by Amenhotep III and Ramses II, is a temple of celebration. Unlike Karnak, which was for the gods, Luxor was the temple of the annual Opet Festival, where the cult images of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu from Karnak would be brought on a procession to “reunite” with Amun-Re at Luxor. The temple’s obelisk (one of which now stands in Paris) and the colossal statues of Ramses II at its entrance are iconic. Its graceful papyrus-shaped columns and serene courtyards feel more elegant and intimate than the massive scale of Karnak.

Karnak Temple is a city of temples, the largest religious complex in the world. It was the chief place of worship for the Theban Triad (Amun, Mut, and Khonsu) and served as the center of religious life for the New Kingdom. The complex grew over centuries, with nearly thirty pharaohs contributing to its construction. The most breathtaking feature is the Great Hypostyle Hall, a forest of 134 towering columns, each one covered in detailed reliefs and hieroglyphs. Walking through this hall is a humbling experience, as the immense scale of the architecture makes one feel minuscule. Obelisks, statues, and smaller shrines are scattered throughout the site, each telling a piece of the story of Egyptian religion and power.

The Valley of the Kings: The Final Journey

While not a temple in the traditional sense, a trip down the Nile would be incomplete without a visit to the Valley of the Kings. Situated on the West Bank of the Nile, across from Luxor, this is where the pharaohs of the New Kingdom were buried in rock-cut tombs.

This shift from pyramid building was a move to protect the royal tombs from looters. The tombs are a work of art in themselves, with their walls covered in elaborate and colorful murals from the Book of the Dead and other funerary texts. These murals provided the deceased with the spells and knowledge needed to navigate the treacherous underworld and achieve eternal life. The discovery of Tutankhamun’s nearly intact tomb in this valley in 1922 was one of the most significant archaeological finds of all time. ConclusionA voyage down the Nile reveals that the ancient Egyptians saw the river not just as a source of life, but as a symbolic path to eternity. The temples on its banks are not random monuments; they are points on a sacred map. From the self-aggrandizing statues of Abu Simbel to the dual symmetry of Kom Ombo, the preservation of Edfu, and the awe-inspiring scale of Karnak, each temple tells a different part of the Egyptian history. They stand as eternal sentinels, silent observers of the river’s flow, and enduring symbols of a civilization that built with a vision for immortality. The journey is a profound reminder that the power of belief, artistry, and engineering can transcend time itself. The Nile continues to flow, and with it, the stories of the pharaohs live on in stone and memory.

Leave a Reply