Abstract

This article surveys recent archaeological discoveries and scholarly interpretations concerning several of Egypt’s major temples along the Nile—Abu Simbel, Kom Ombo, Luxor, Karnak, and Philae. New evidence, ranging from painted relief blocks, storage and workshop complexes, to inscriptions from Ptolemaic co-regencies, helps refine our understanding of religious, political, and economic roles of these temples. The aim is to integrate recent fieldwork into the broader context of ancient Egyptian architectural, ritual, and administrative practices.

1. Introduction

Temples in ancient Egypt were more than devotional sites: they were centers of economic activity, political symbolism, ritual innovation, and artistic expression. While classical Egyptology has long studied them, recent archaeological work has yielded fresh material, allowing refinements in dating, function, and meaning. This article reviews recent findings (2024-2025) at key temple complexes, and considers how these findings inform our understanding of ancient religion, statecraft, and architectural technology.

2. Abu Simbel: Architecture, Relocation, and Symbolism

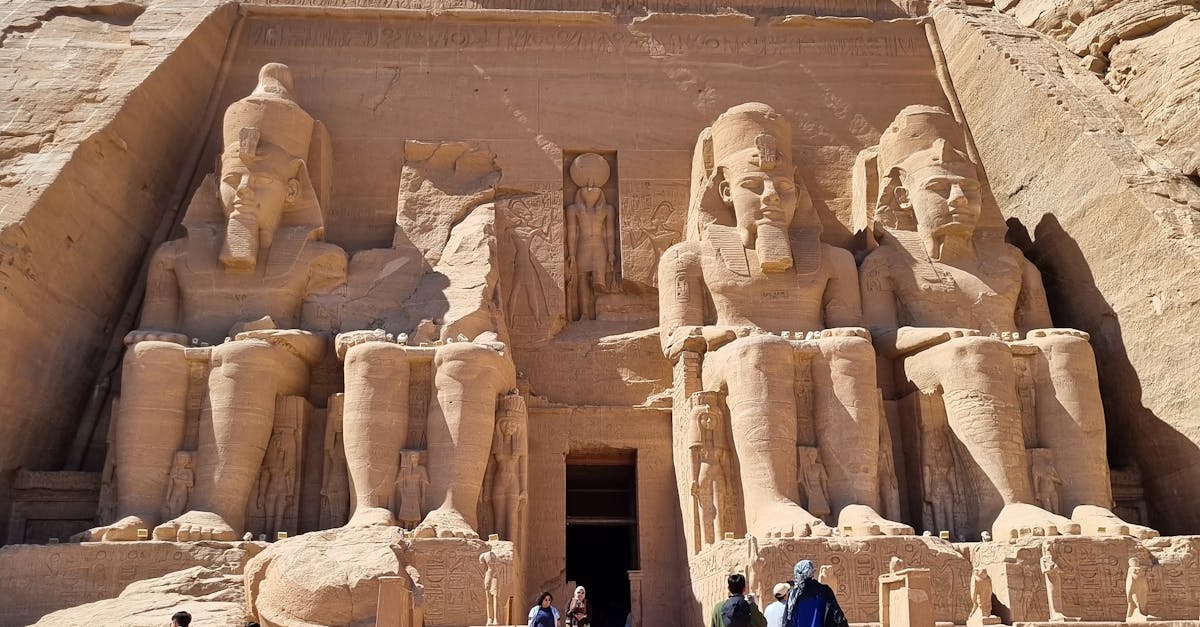

2.1 Architectural language and genius loci

A recently published study by Nelly Ramzy (Sinai University) provides a hermeneutic analysis of the Great Temple at Abu Simbel (Ramses II’s temple in Nubia). The study argues that many aspects taken as religious tradition—orientation, proportions, location—also serve political functions. For example, the placement far in Nubia was both a statement of territorial control and a visible divine presence at the boundary of Egypt’s dominion. The notion of genius loci (spirit of place) is applied to consider how the cliff, the Nile, and the sky combine with the statues and reliefs to project power.

2.2 Relocation engineering and astronomical alignments

The 1960s relocation of Abu Simbel to escape inundation from the Aswan High Dam is well-documented. Technical reports show that the temples were moved 65 meters higher and 200 meters back from the river. Precision was crucial—so much so that the orientation relative to cardinal points and light paths had to be preserved. One aim was to ensure that, at specific dates (equinoxes and solstices), sunlight still penetrated to the inner sanctuaries, illuminating statues and reliefs just as in their original location. Deviations of more than 5 mm in key alignments were avoided.

3. Kom Ombo: Ptolemaic Additions and Divine Children

Recent studies at Kom Ombo have brought new material evidence to the Ptolemaic period. One published article (Ali Abdelhalim, Ain Shams University) examines a column now in the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) (catalogue number 45,481), showing Cleopatra III offering to deities alongside her son Ptolemy IX. Several features are noteworthy:Representation of Mammisi (birth houses) motifs: the “divine children” of Kom Ombo appear in the reliefs, a motif common in Ptolemaic sanctuaries connected with royal birth and legitimization. Decorative elements such as Hathoric faces and Rekhyt birds are used in association with the divine children, confirming hybridity of traditional Egyptian symbolic motifs and Ptolemaic royal ideology.Palaeographical analysis of hieroglyphic signs suggests coregency periods (overlap of rule by mother and son) at Kom Ombo. These details refine chronological models of Ptolemaic co-rule.

4. Luxor Region: Deir el-Bahari, Ramesseum, Karnak

4.1 Deir el-Bahari & the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut

An expedition by the Zahi Hawass Foundation and the Supreme Council of Antiquities has unveiled over 1,000 to 1,500 decorated stone blocks from the foundation wall of Hatshepsut’s Valley Temple, along the causeway in Deir el-Bahari. These blocks include vibrant bas-reliefs showing Hatshepsut and her successor Thutmose III participating in ritual activities. In addition:A limestone tablet bearing the name of her architect, Senenmut, was found, confirming accounts from inscriptions and supporting traditional attributions of design responsibility. Rock-cut tombs, burial shafts from the 17th Dynasty, and items such as amulets, funerary masks, and small objects (toys, scarabs) were found nearby. These point to the necropolis function around the temple and continuation of burial practice into later periods. These findings help bridge some of the gaps between the Middle Kingdom, Second Intermediate Period, and New Kingdom transition, clarifying which artistic and ritual practices persisted or changed across dynasties.

4.2 Ramesseum: Economy, Education, and Daily Life

The Ramesseum (the “Temple of Millions of Years” of Ramses II) has yielded particularly rich new data:Discovery of a House of Life (Per-Ankh) inside the temple premises: long hypothesized in texts as temple-attached schools or scribal/ritual education centers, this is the first material evidence that provides layout, artifacts (students’ drawings, game pieces), and tools of learning. Identification of economic infrastructure: storage facilities for olive oil, honey, fats, wine (with wine jar labels), kitchens, bakeries, textile and stone workshops. These suggest that the temple complex was a self-sustaining institution with both ritual and economic dimensions. Tombs from the Third Intermediate Period in the temple’s vicinity, containing canopic jars, funerary tools, and large numbers (401) of ushabti figurines. This indicates that the temple’s necropolis function was active well into later periods, and that religious and funerary practice remained intertwined with temple activity.

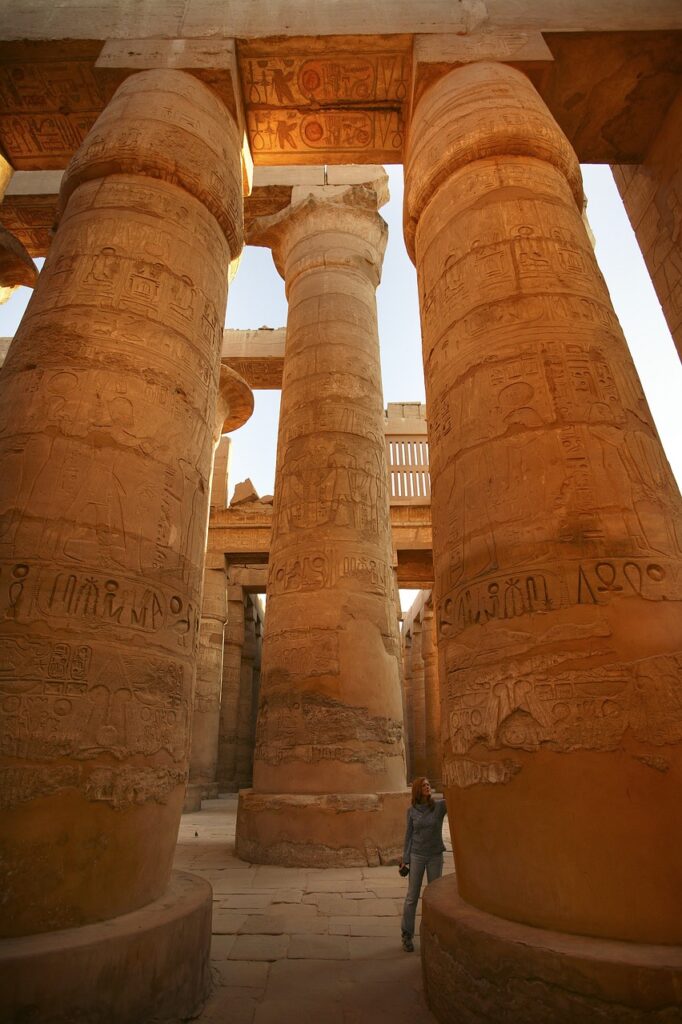

4.3 Karnak: Southern Chapels, Restoration, and Material Remains

At Karnak, restoration work was recently concluded on the Southern Chapels of the Akh Menu Temple, under the Egyptian-French Centre for Study of Karnak Temples (CFEETK). These chapels, previously less accessible to the public, contain inscriptions and ritual scenes that had been poorly preserved. Their restoration enhances understanding of the complexity of temple ritual space and visitor/cultic access in pharaonic times. Also at Karnak, in the Naga Abu Asba site, excavators uncovered a large mudbrick wall stamped with the names of King Menkheperre (21st Dynasty) and his wife. Adjacent bronze workshops, foundries, and beer or wine production areas suggest a significant industrial zone affiliated with the temple complex.

5. Philae: (Note on Recent Research)

While the most intense recent reports have focused on Luxor, Karnak, Kom Ombo, and Abu Simbel, Philae remains crucial in studies of religious endurance and transition (from Ptolemaic through Roman to Christian eras). As of this writing (2025), recent published fieldwork at Philae has not matched the scale of new excavation reports from Luxor, but conservation work continues, particularly on inscriptions and reliefs that document changes in worship of Isis and her cult’s interactions with Roman and later Christian religious institutions. (Future articles are expected.)

6. Discussion

6.1 Temples as Multifunctional Institutions

The recent findings underscore that temples in ancient Egypt were not solely religious centers. The Ramesseum evidence in particular shows temples functioned as economic hubs, workshops, storage and redistribution entities, educational centers (Houses of Life), and necropolises. The boundary between sacred space and mundane utility was porous.

6.2 Dynastic Continuities and Change

Findings around Deir el-Bahari and Kom Ombo contribute significantly to understanding transitions between dynasties:

- The art, relief style, and iconography of Hatshepsut’s blocks clarify how she justified her reign and represented her office in relation to Thutmose III, including recurring ritual motifs.

- The column at Kom Ombo bearing Cleopatra III and Ptolemy IX provides evidence for co-regency practice, and incorporation of traditional Egyptian religious imagery even in Ptolemaic rulership.

6.3 Architectural Techniques, Restoration, and Relocation

The engineering feats at Abu Simbel’s relocation, and precise requirements for preserving light paths, are echoes of ancient concerns with astronomical alignment, ritual timing, and spatial symbolism. Restoration at Karnak and Luxor likewise seeks not just to stabilize stone, but to recover inscriptions and imagery which inform us of religious rituals, festival processions, and temple organization.

6.4 Question of Dating and Periodization

Artifacts such as wine jar labels, inscriptions, funerary objects and amulets (in Ramesseum, Deir el-Bahari etc.) provide more precise dating anchors, helping fill gaps especially in lesser-known periods like the 17th Dynasty, Third Intermediate Period, or during times of political upheaval (Hyksos period). New finds also inform us about non-royal elites (temple administrators, overseers) and their roles.

7. Conclusion

New Egyptological research and excavation in the years around 2024-2025 demonstrate that ancient Egyptian temples along the Nile remain fertile ground for discovering how religion, politics, and daily life intertwined. From the political symbolism embedded in colossal temples like Abu Simbel, through dual deity worship at Kom Ombo, to the emerging evidence for temple schools and economy at the Ramesseum, scholarship is deepening our appreciation of how layered these institutions were.

Future work, particularly at lesser-excavated temples such as Philae or more remote Nubian sites, promises to fill further lacunae—especially concerning the interplay of local cults, regional administration, and how temples adapted under Ptolemaic, Roman, and later Christian rule.

References (Selected Recent Excavations and Studies)

- Ramzy, Nelly. “The Genius Loci at the Great Temple of Abu Simbel: Hermeneutic Reading in the Architectural Language of Ancient Egyptian Temples of Ramses II in Nubia.” Journal of Ancient History & Archaeology, 2024. jaha.org.ro

- Abdelhalim, Ali. “The Column of Cleopatra III and Ptolemy IX from Kom Ombo in the Grand Egyptian Museum.” SHEDET: Journal of the Faculty of Arts, Ain Shams University, 2021. Shedet

- Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities / Zahi Hawass Foundation. Discovery of decorated stone blocks, tombs, and artifacts at Hatshepsut’s Valley Temple, Luxor, 2025. Al Arabiya English+3Reuters+3Ahram Online+3

- Joint Egyptian-French mission at the Ramesseum: discoveries of House of Life, storage complexes, workshops, tombs, ushabti figurines, etc. Archaeology News Online Magazine+2Egypt Monuments+2

- Restoration of Southern Chapels of Akh Menu Temple, Karnak; industrial remains at Naga Abu Asba, Luxor. Ahram Online+1

Leave a Reply